There is nothing that kills a conversation quite as effectively as the words ‘my sister died.’

When asked how many siblings I have, I always say that I was one of four. Or that I have three siblings; or that I have two sisters and one brother. It’s only when people ask where my siblings live, or how old they are, that things can get awkward.

People are always shocked. And then they want to know when, and how old she was, and how (2004; sixteen; drowning). And then they often say that they’re sorry they brought it up, that it must be hard for me to talk about. And then we move on.

The thing is, it’s not hard to talk about it. What’s hard is that it happened. Talking about her is lovely. I want to talk about her. I’m just not so sure that other people do.

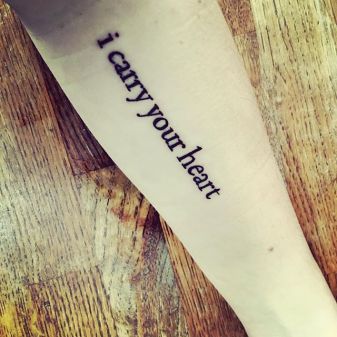

I had a tattoo for Helen this week. I guess it’s my way of memorialising her. We have lots of ways of doing that, us humans- and many of them are public.

Flowers in cellophane are tied to lamp-posts, with a photo that eventually fades in the sun and turns to mush around the edges in the rain. Trees are planted, and songs written, and plaques screwed to benches, and Facebook pages created. The Taj Mahal was built by a grieving husband as a monument to his wife (the fact that she was just one of his several wives takes away some of the romance, but let’s gloss over that…).

For me, written words have been my way of creating a memorial for Helen. I have always loved writing, but losing Helen cut something open in me, and words poured from that place. Notebooks are filled with long letters to Helen and short (bad) poems and angry scribbles. There are folders of writing about Helen tucked away on the laptops I have used over the last twelve-and-some years. And there are pockets of my grief dripped like spots of ink across the internet.

So it made sense to me to use words (EE Cumming’s words) to memorialise Helen in a tattoo. But why did I write it on my skin, forever? Why not just read the poem, or have it framed? Why do so many people get tattoos in memory of someone they have lost?

Most obviously, of course, it’s about honouring the person with something permanent and indelible. My tattoo will last as long as my love and grief for Helen will last- that is, as long as I am living. It’s about making Helen present, somehow.

But there’s something else, too. For me, it’s the same as the roadside memorials, or the Taj Mahal. It’s about making private grief public.

There’s a short period of mourning after a death, when it is demanded of you to outwardly grieve, to talk, to emote. But when the world perceives that the immediate, acute wound has healed over, that’s the end of that. And never mind the scarring that remains. Normal life can cover that up like a heavy-duty concealer.

Often when I’ve written a blog about grief, I’ll get messages from people I know. ‘My sister died too.’ ‘It was like that for me, when my husband died.’ More often than not, if they are a newer friend or a work colleague, I’ll have had no idea that they went through this loss. You can’t tell, from looking at someone, what they are carrying around with them. You can’t tell from the outside if someone’s heart has been shattered, and cobbled back together.

So maybe having a tattoo, or tying bunches of flowers to a lamp-post, or drinking a little too much gin on the eve of an anniversary and misery-posting twenty photos of your loved one onto Facebook, is, in part, wanting to signal your loss, to show that you haven’t come to terms with it, or got over it, and that you never will.

I feel uncomfortable writing this, but let’s grasp the truthy nettle: I do want my grief to be recognised. More than that, I want grief, generally, to be recognised and spoken about. Not just to rear up for a few days of stricken hashtagging and tortured newspaper think-pieces when a famous person dies. Or to be packed away along with the funeral outfit that you never want to look at again.

Look, I don’t want to lie on a chaise longue and weep about my sister all day. But I do wish that we could talk about grief as easily as we talk about birth, or love, or Kimye. Let’s face it, a conversation about sex is far more likely to happen in an office environment than a conversation about grief, and something about that seems off to me.

So, in the interests of talking about loss- and if you’ve made it this far- this is what it’s like, for me, almost thirteen years down the road of grief:

I miss her every day. (See, sometimes words are so over-used that they don’t do the job unless you dig into their meaning. I miss her. Every day. If you know what that feels like- here, have an awkward hug from me. If you don’t, can you imagine? Missing someone, every day. The constant hum of something like homesickness. The longing.)

I cry for her every day. Crying doesn’t necessarily mean tears. Sometimes it’s a heavy fullness in my chest when I am washing up. Or sometimes it’s a messy, snotty sob fest into my pillow- and that kind of crying, actually, feels the best.

I can’t believe it. I still can’t believe it.

I can be happy- I am happy- but I’ll never not be sad.

I’ll love her until the end of time.

And, always, I carry her heart (I carry it in my heart).

I can only speak of my own experience. But if you know someone who is bereaved- even if it happened a long time ago, and even if they haven’t built a marble palace or injected ink into their skin to make their private grief public – maybe ask them about it sometime. The chances are, they miss their loved one every day too.